How POSRG Supports Sales With Sustainability

By Matt Pillar, chief editor

This POS VAR’s status as one of the only certified facilities dedicated to the recycling and destruction of POS equipment and data is accelerating its perennial double-digit growth.

Ten years later, Polich oversees an electronics recycling and data destruction program at POSRG that occupies a large swath of the $22 million company’s 80,000 square feet of real estate. Its 70 employees occupy offices in Chicago, NY, and Burlington, Ontario. Its more than 3,000 global customers have fueled annual double-digit growth rates.

Testa enjoyed a long and lucrative VP of sales position with Vision POS, where his account roster included the likes of Macy’s, Petsmart, and Home Depot. In 2005, he retreated to his basement to launch POSRG, which found him buying used POS stations, reformatting them, and shining them up before pushing them out for sale to the local small to midsize retail market.

Polich, a self-described environmentalist, came to the company with schooling in marine ecology and work experience that included turning wrenches as a pipefitter, building office cubicles, and working as a special education teacher’s aide.

CMO Jim Remke jumped on board shortly after Polich, when it became clear that the company’s growth trajectory was poised for takeoff. Remke’s education and work background are in marketing, but like Polich, POS technology and the retail industry were new subject matter.

Equally new to Remke and Polich were electronics recycling and data destruction, both of which arose as a byproduct of the POSRG model. When you buy a giant lot of used POS stations that K-Mart and Sears will no longer need, and you start taking them in by the truckload, there’s going to be some e-junk you can’t use but which needs to be recycled. Some of that e-junk is going to have data on it that needs to be destroyed.

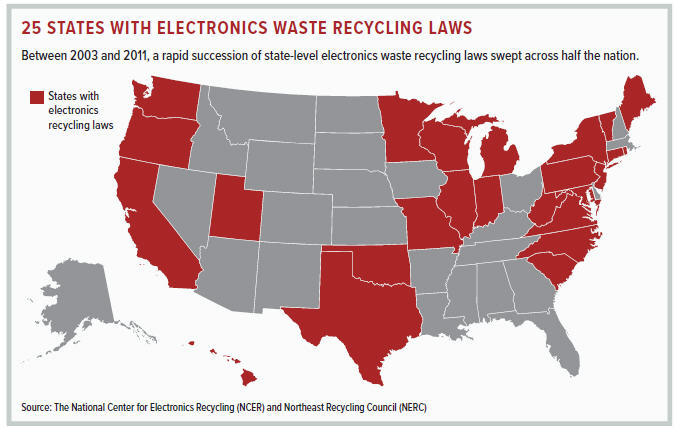

In addition to federal mandates, 25 U.S. states currently have electronics recycling laws that put even more stringent requirements on the disposal of electronic equipment than the feds do. The specific details of each federal and state law can be found under the State Law Data tab on the Electronics Recycling Coordination Clearinghouse website at eCycleClearingHouse.org.

As VP of asset disposition, it’s Polich’s job to make sure that the roughly 120 tons of POS gear that moves through POSRG facilities each month are refurbished or recycled with as little waste as possible — and that the digital data coming in the company’s doors never sees its way out.

Polich has been in large part responsible for building the exemplary e-waste and data destruction program at POSRG, but it hasn’t been an easy mission. “When I came on board, we were spending a lot of money sending equipment that couldn’t be refurbished off to the recycler,” says Polich. “We were paying several hundred dollars per pallet for the removal of recyclable electronics, and we’d often have five to 10 pallets per month, costing us thousands.”

Those are head scratch-worthy sums. Sure, electronics contain some hazardous waste — namely lead and mercury — and containing and mitigating the environmental impact of those hazards comes with a price tag. But, there’s also some pretty valuable stuff in those boxes. Circuit boards, CPUs, and various smaller electronic device components are constructed using gold, silver, platinum, palladium, copper, nickel, and several lesser known precious and semi-precious metals. If those could be isolated, wouldn’t they at least chip away at the cost of electronics disposal? “We went to a recycling conference, and we realized that disposal of this equipment should look a lot more like a money maker than a cost of doing business,” says Polich.

What’s more, some strange market dynamics were beginning to impact the POSRG business model, which is dependent on picking up bulk lots of used POS units and peripherals that can be refurbished at a price that leaves room for a healthy margin upon their resale. The company examines the equipment in advance of purchase, noting that anywhere from 20 to 40 percent of a buy will be destined for the recycling bin as opposed to remarketed.

“We noticed a downward trend in the availability of serviceable used equipment directly from end users and a spike in the availability of that equipment from recyclers who were trying to sell it to us,” says Remke. “That was increasing our cost of acquisition, decreasing the end user’s return, and in fact costing the end user money to have its unserviceable equipment picked up by a different company for recycling,” he says. “In some cases, the end user had to pay to get it gone and we had to pay to get it back, so the recycler was getting paid twice for a single piece of equipment,” he explains. Remke and Polich determined that POSRG could provide all the same services at a much lower cost to the end user. In fact, POSRG would pay for good serviceable equipment and take the equipment that’s beyond repair and destined for the recycle bin at no charge. That’s when POSRG got serious about putting a system in place to break used electronics down into their individual components before sending them for recycling, which maximizes the value of each individual element in the box.

THE COSTS AND OPPORTUNITIES OF COMPLIANCE

With the cost to dispose of its unrepairable electronics dropping dramatically — effectively accomplishing mission number one — POSRG sought to further leverage its newfound commitment to sustainability. There’s market value in certified sustainability practices. Beyond the altruistic feel-good PR it generates, many national and global retail brands are imposing their own sustainability standards on their upstream and downstream trading partners. Walmart, for instance, could refuse to carry a product if the manufacturer of that product doesn’t conform to its minimal packaging standards. Likewise, it could refuse to sell thousands of used POS stations and peripheral equipment to POSRG if the company’s recycling and disposal practices didn’t align with Walmart’s 2025 Zero Waste goal. Pressure on brands like Walmart to enforce such policies doesn’t just come from the public. The EPA itself “encourages” corporations to opt for certified recyclers, such as those endorsed by the EPA’s two standards programs: e-Stewards and R2 (Responsible Recycling).

Polich set out to ensure POSRG possessed the accreditations it would need to do business with tier-one retail, beginning with the R2 certification.

To put things into context, certifications like R2 don’t come cheap and easy. They require capital outlay to outfit recycling and data destruction facilities with the physical equipment, trained personnel, and operational procedures required to obtain and maintain certifications. Among other requirements laid out in the 25- page SERI (Sustainable Electronic Recycling Institute) R2 Certification prep checklist, certified recyclers must create and adhere to an incredibly detailed EHSMS (Environmental, Health, and Safety Management System); they must audit 100 percent of their approved downstream vendors; they’re responsible for ensuring that their haulers have clean three-year driving records; and they must retain commercial contracts and bills of lading for all equipment, components, and materials coming into and out of the facility for a minimum of three years. Those are just four of the 191 requirements laid out by SERI.

Polich had the people and the expertise. He had the processes in place. But POSRG didn’t have a compliant facility. “The building we were operating in didn’t meet the requirements because we couldn’t lock it down in a way that completely isolated the equipment and data that we were recycling and destroying from the general population of our workforce,” explains Polich. “To obtain certification in that facility, we would have been required to subject our entire staff to background checks and drug screening, as opposed to just those associates handling data destruction responsibilities.” Deeming that an unfeasible option, POSRG decided the only way to honor its commitment to R2 was to expand into a bigger facility and lock it down.

Today, POSRG is R2 certified. In addition to the costs of real estate and security, the company engaged a paid R2 consultant to help Polich scope out the project. It invested six months of training in its recycling center employees.

POSRG is also an ISO 14001 and OHSAS 18001 accredited company. Those certifications direct its approach to the auditing, communications, labeling, and life cycle analysis work associated with its electronics recycling business. It’s also a member of the Illinois Recycling Association. All this cost and effort is in addition to the direct cost of certification maintenance. To maintain its status as one of the 600 R2-certified electronics recycling facilities worldwide, for instance, POSRG pays an annual licensing fee of $1,500 and subjects itself to annual audits for compliance with the R2:2013 Standard at a cost of roughly $6,000 per year. If a standard isn’t being met, corrective action must be taken at the risk of having its certification revoked.

When all is said and done, says Polich, the recycling center’s operating costs are about $300,000 per year and inching closer to break-even. “The only income we recognize is the service fees we collect for data destruction and the market value of the commodities we sell downstream. Anything that can be refurbished and remarketed goes to our other facility for resale, which is our profit center.”

DATA DESTRUCTION AS A SERVICE

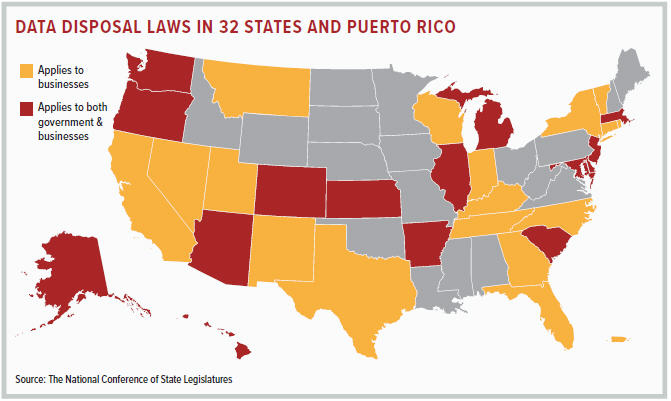

The retail industry and the tech service providers who serve it are no stranger to the dangers of collecting and storing personal identifying information. As if the risk of brand damage and litigation associated with exposing consumer data isn’t great enough, at least 32 states and Puerto Rico have enacted laws that require entities to destroy, dispose, or otherwise make personal information unreadable or undecipherable.

The Federal Trade Commission’s Disposal Rule also requires proper disposal of information in or derived from consumer reports and records to protect against “unauthorized access to or use of the information.”

To that end, POSRG is also a NAID (National Association for Information Destruction) AAA certified facility for physical destruction of hard drives. “We offer discreet and confidential elimination of all data using the same standard as the DOD (Department Of Defense), which requires a 3 or 7 pass write-over, degaussing (eliminating a disk’s magnetic field), physical shredding of the disk, or any combination of those techniques,” says Polich.

NAID AAA certification is acknowledged by many accreditation programs, such as those offered by the International Association of IT Asset Managers (IAITAM), the Institute of Certified Records Managers, and the aforementioned R2 IT asset recycling program certification offered by the Sustainable Electronic Recycling Institute (SERI). Again, the approved supplier chain effect comes into play here for POSRG. If the IAITAM’s global presence of thousands of IT asset managers deems NAID AAA certification a requirement of membership, it behooves POSRG to maintain the standard.

DOES ELECTRONICS RECYCLING PAY?

On its website, the EPA extols the benefits of becoming an electronics recycler as follows:

Reducing environmental and human health impacts from improper recycling, increasing access to quality reusable and refurbished equipment to those who need it, and reducing energy use and other environmental impacts associated with mining and processing of virgin materials, conserving our limited natural resources.

These benefits assume electronics recyclers are motivated more by altruistic intentions than capitalism. That’s not the case at POSRG. The company has been achieving double-digit YOY growth since its 2005 inception. To keep that momentum rolling, it can’t let a low-to-no-profit, resource-intensive operation drain its bottom line, no matter how well-intentioned. So is its recycling initiative making money? Remke says no — not as a direct line of business, anyway. But, he says, POSRG can justify the offering because it does positively impact the bottom line by exposing the company to specific customers and larger markets that need, or as mentioned earlier, require the service.

“Most of the equipment that comes in for refurbishment, recycling, and data destruction services is received from the retailers we do business with, but we do provide the service for myriad non-retail businesses in Chicagoland, Wisconsin, and Northern Indiana,” says Remke. In addition to retail, the company has done asset disposition and data destruction work for financial and insurance institutions, law firms, banks, and healthcare. Remke says the company is intent on growing its recycling and data destruction services and that it recently hired an outside sales representative whose sole focus is selling these services. You can bet they’ll be selling them to tier-one retail and hospitality establishments, whose business they want on the POS value-added resale side of the business. While POSRG made its name selling refurbed units to small businesses, it also sells new equipment to big businesses from a host of manufacturers. Its electronics recycling and data destruction initiatives and certifications are giving it a leg up on serving those big businesses for the duration of their product life cycles; when they have old equipment that they’re paranoid about disposing of, POSRG destroys data and recycles that equipment in an accredited fashion, then turns around with the sale of new stuff. “We’ve developed a number of national accounts on the new and refurbished VAR side that started with our recycling and data destruction services,” says Polich.

About a decade ago, Polich and Remke went to work for a small VAR that was emerging from its owner’s basement. Today, Polich is managing hardware recycling and data destruction for some of the biggest retail and hospitality brands in the country, and Remke is queuing up the sale of new POS equipment. Collectively, they’re supporting client sustainability mandates along the way by providing cradle-to-grave services to support the entire hardware life cycle.